Israels tilbagetrækning fra Gazastriben

Den israelske tilbagetrækning fra Gazastriben (Hebraisk: תוכנית ההתנתקות, transskription: Tokhnit HaHitnatkut, direkte oversat: "Frigørelsesplanen") var en ensidige israelsk tilbagetrækning i 2005, hvor 21 israelske bosættelser i Gazastriben blev demonteret og beboerne evakueret blev evakueret ud af Gazastriben af den israelske hær.

Tilbagetrækningen fra Gazastriben blev foreslået i 2003 af den daværende premierminister Ariel Sharon. Forslaget blev vedtaget af regeringen i juni 2004 og godkendt af Knesset i februar 2005 som "Disengagement Plan Implementation Law" (dansk: "Lov om gennemførelse af frigørelsesplan").[1] Loven blev begyndt implementeret i august 2005, og blev færdigimplementeret i september 2005.

De israelske bosættere, der nægtede at acceptere regeringens kompensationspakker og frivilligt forlade deres hjem i Gazastriben inden den fremsatte frist den 15. august 2005, blev med tvang udflyttet af israelske sikkerhedsstyrker.[2] Udflytningen af alle beboere, nedrivning af beboelsesbygninger samt evakuering af tilhørende sikkerhedspersonale fra Gazastriben blev alt sammen afsluttet den 12. september 2005.[3] Ligeledes blev fire israelske bosættelser i den nordlige del af Vestbredden nedrevet og indbyggerne heraf genhuset. 8.000 jødiske bosættere fra de 21 bosættelser i Gazastriben blev i alt genhuset. De israelske bosættere modtog i gennemsnit mere end $200.000 i kompensation pr. familie.[4]

FN, internationale menneskerettighedsorganisationer og mange juridiske forskere mener fortsat, at Gazastriben er under militær besættelse af Israel.[5] Dette bestrides dog af Israel og andre juridiske lærde.[6] Efter tilbagetrækningen har Israel fortsat med at opretholde direkte kontrol over Gazastribens søfarts- og luftrum. Ligeledes kontrollerer Israel seks af Gazastribens syv landbaseret grænseovergange, opretholder en no-go bufferzone inden for territoriet og kontrollerer det palæstinensiske befolkningsregister. Gazastriben er fortsat afhængig af Israel for dets forsyning af vand, elektricitet, telekommunikation og andre fornødenheder.[5][7]

Rationale og udvikling af politikken[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

I sin bog "Sharon: The Life of a Leader" skrev den israelske premierminister Ariel Sharons søn Gilad, at han gav sin far ideen om tilbagetrækningen.[8] Sharon havde oprindeligt navngivet tilbagetrækningsplan, "adskillelsesplanen" eller "Tokhnit HaHafrada", inden han indså, at "adskillelse" lød dårligt – især på engelsk – "fordi det fremkaldte [associationer til] apartheid".[9]

I et interview fra november 2003 forklarede Ehud Olmert – Sharons næstformand – som i to eller tre måneder havde givet hints om den nye tilgang, sin politik som følger:[10][11][12]

Der er ingen tvivl i mit sind om, at Israels regering meget snart bliver nødt til at tage fat på det demografiske problem med den største seriøsitet og beslutsomhed. Dette spørgsmål vil frem for alt andet diktere den løsning, vi skal vedtage. I mangel af en forhandlet aftale – og jeg tror ikke på de realistiske udsigter til en aftale – er vi nødt til at implementere et ensidigt alternativ... Flere og flere palæstinensere er uinteresserede i en forhandlet to-statsløsning, fordi de ønsker at ændre essensen af konflikten fra et algerisk paradigme til et sydafrikansk. Fra en kamp mod 'besættelse' i deres sprogbrug til en kamp for én-mand-én-stemme. Det er selvfølgelig en meget renere kamp, en meget mere folkelig kamp - og i sidste ende en meget mere magtfuld kamp. For os ville det betyde enden på den jødiske stat... parametrene for en ensidig løsning er: At maksimere antallet af jøder; at minimere antallet af palæstinensere; ikke at trække sig tilbage til 1967-grænsen og ikke at dele Jerusalem... For 23 år siden foreslog Moshe Dayan ensidig autonomi. På samme bølgelængde bliver vi måske nødt til at gå ind for ensidig adskillelse... [det] ville uundgåeligt udelukke en dialog med palæstinenserne i mindst 25 år.[13]

Sharon foreslog sin tilbagetrækningsplan for første gang den 18. december 2003 på den fjerde Herzliya-konference. I sin tale til konferencen udtalte Sharon, at ″bosættelser, der vil blive flyttet, er dem, der ikke vil omfatte staten Israels territorium inden for rammerne af en eventuel fremtidig permanent aftale. Samtidig vil Israel inden for rammerne af tilbagetrækningsplanen styrke sin kontrol over de samme områder i landet Israel, som vil udgøre en uadskillelig del af staten Israel i enhver fremtidig aftale.″[14]

Sharon annoncerede formelt planen i sit brev den 14. april 2004 til den amerikanske præsident George W. Bush, hvori han udtalte, at "der ikke eksisterer nogen palæstinensisk partner med hvem man kan gå fredeligt frem mod en løsning".[15]

Den 6. juni 2004 godkendte Sharons regering en ændret tilbagetrækningsplan, men med det forbehold, at afviklingen af hver enkelt bosættelse skulle stemmes separat. Den 11. oktober, ved åbningen af Knesset-vintermødet, skitserede Sharon sin plan om at påbegynde lovgivning for tilbagetrækningen i begyndelsen af november. Den 26. oktober gav Knesset sin foreløbige godkendelse. Den 16. februar 2005 færdiggjorde og godkendte Knesset planen.

I oktober 2004 forklarede premierminister Ariel Sharons seniorrådgiver, Dov Weissglass, betydningen af Sharons udtalelse yderligere:

Betydningen af tilbagetrækningsplanen er en fastfrysning af fredsprocessen, og når man fastfryser den proces, forhindrer man oprettelsen af en palæstinensisk stat, og man forhindrer en diskussion om flygtningene, grænserne og Jerusalem. Faktisk er hele denne pakke kaldet den palæstinensiske stat, med alt hvad den indebærer, blevet fjernet på ubestemt tid fra vores dagsorden. Og alt dette med autoritet og tilladelse. Alt sammen med en præsidentiel velsignelse og ratificering af begge kongreshuse. Det er præcis, hvad der skete. Du ved, udtrykket 'fredsproces' er en samling af koncepter og forpligtelser. Fredsprocessen er etableringen af en palæstinensisk stat med alle de sikkerhedsrisici, det medfører. Fredsprocessen er evakuering af bosættelser, det er tilbagevenden af flygtninge, det er opdelingen af Jerusalem. Og alt det er nu blevet frosset.... Det, jeg reelt gik med til med amerikanerne, var, at en del af bosættelserne slet ikke ville blive behandlet, og resten vil ikke blive behandlet, før palæstinenserne bliver til finner. Det er betydningen af det, vi gjorde.[16]

Demografiske bekymringer, opretholdelsen af et jødisk flertal i israelsk-kontrollerede områder, spillede en væsentlig rolle i udviklingen af politikken.[17][18][19]

Et rationale for tilbagetrækningen er delvist blevet tilskrevet Arnon Soffers kampagne, som gik på den "fare den palæstinensiske livmoder udgjorde for det israelske demokrati."[20] Sharon nævnte den demografiske begrundelse i en offentlig tale den 15. august 2005 – dagen for tilbagetrækningen – hvori han bl.a. udtalte: "Det er ingen hemmelighed, at jeg ligesom mange andre havde troet og håbet, at vi for evigt kunne holde fast i Netzarim og Kfar Darom. Men den ændrede virkelighed i landet, i regionen og verden krævede af mig en revurdering og ændring af holdninger. Vi kan ikke holde fast i Gaza for evigt. Mere end en million palæstinensere bor der og fordobler deres antal med hver generation."[21][22] Samtidig udtalte Shimon Peres, daværende vicepremierminister, i et interview, at: "Vi trækker os fra Gaza på grund af demografi".[22]

Fortsat kontrol over Gazastriben blev af nogle anset for at udgøre et umuligt dilemma med hensyn til Israels evne til at forblive en jødisk og demokratisk stat i alle de områder, som det kontrollerer.[23][24]

Se også[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

Referencer[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

- ^ "Knesset Approves Disengagement Implementation Law (February 2005)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ^ "Jewish Settlers Receive Hundreds of Thousands in Compensation for Leaving Gaza". Democracy Now. 16. august 2005. Arkiveret fra originalen 9. maj 2007. Hentet 5. maj 2007.

- ^ "Demolition of Gaza Homes Completed". Ynetnews.com. 1. september 2005. Hentet 5. maj 2007.

- ^ Rivlin, Paul (2010). The Israeli Economy from the Foundation of the State through the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. s. 245. ISBN 9781139493963.

- ^ a b Sanger, Andrew (2011). "The Contemporary Law of Blockade and the Gaza Freedom Flotilla". I M.N. Schmitt (red.). Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law 2010. Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law. Vol. 13. Springer Science & Business Media. s. 429. doi:10.1007/978-90-6704-811-8_14. ISBN 978-90-6704-811-8.

Israel claims it no longer occupies the Gaza Strip, maintaining that it is neither a State nor a territory occupied or controlled by Israel, but rather it has 'sui generis' status. Pursuant to the Disengagement Plan, Israel dismantled all military institutions and settlements in Gaza and there is no longer a permanent Israeli military or civilian presence in the territory. However the Plan also provided that Israel will guard and monitor the external land perimeter of the Gaza Strip, will continue to maintain exclusive authority in Gaza air space, and will continue to exercise security activity in the sea off the coast of the Gaza Strip as well as maintaining an Israeli military presence on the Egyptian-Gaza border, and reserving the right to reenter Gaza at will. Israel continues to control six of Gaza's seven land crossings, its maritime borders and airspace and the movement of goods and persons in and out of the territory. Egypt controls one of Gaza's land crossings. Gaza is also dependent on Israel for water, electricity, telecommunications and other utilities, currency, issuing IDs, and permits to enter and leave the territory. Israel also has sole control of the Palestinian Population Registry through which the Israeli Army regulates who is classified as a Palestinian and who is a Gazan or West Banker. Since 2000 aside from a limited number of exceptions Israel has refused to add people to the Palestinian Population Registry. It is this direct external control over Gaza and indirect control over life within Gaza that has led the United Nations, the UN General Assembly, the UN Fact Finding Mission to Gaza, International human rights organisations, US Government websites, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and a significant number of legal commentators, to reject the argument that Gaza is no longer occupied.

{{cite book}}: Manglende eller tom|title=(hjælp)

* Scobbie, Iain (2012). Elizabeth Wilmshurst (red.). International Law and the Classification of Conflicts. Oxford University Press. s. 295. ISBN 978-0-19-965775-9.Even after the accession to power of Hamas, Israel's claim that it no longer occupies Gaza has not been accepted by UN bodies, most States, nor the majority of academic commentators because of its exclusive control of its border with Gaza and crossing points including the effective control it exerted over the Rafah crossing until at least May 2011, its control of Gaza's maritime zones and airspace which constitute what Aronson terms the 'security envelope' around Gaza, as well as its ability to intervene forcibly at will in Gaza.

* Gawerc, Michelle (2012). Prefiguring Peace: Israeli-Palestinian Peacebuilding Partnerships. Lexington Books. s. 44. ISBN 9780739166109.While Israel withdrew from the immediate territory, it remained in control of all access to and from Gaza through the border crossings, as well as through the coastline and the airspace. In addition, Gaza was dependent upon Israel for water, electricity sewage communication networks and for its trade (Gisha 2007. Dowty 2008). In other words, while Israel maintained that its occupation of Gaza ended with its unilateral disengagement Palestinians – as well as many human right organizations and international bodies – argued that Gaza was by all intents and purposes still occupied.

- ^ "Is Israel Still an Occupying Power in Gaza?". Netherlands International Law Review. ISSN 0165-070X.

- ^ Peters, Joel (2012). "Gaza". I Caplan (red.). Exit Strategies and State Building. New York: Oxford University Press. s. 234. ISBN 9780199760114.

- ^ "6 years after stroke ariel sharon still responsive son says". The New York Times.

- ^ Steven Poole (2006). Unspeak: How Words Become Weapons, How Weapons Become a Message, and How That Message Becomes Reality. Grove Press. s. 87. ISBN 978-0-8021-1825-7.

- ^ Cook 2006, s. 103.

- ^ Joel Beinin; Rebecca L. Stein (2006). The Struggle for Sovereignty: Palestine and Israel, 1993–2005. Stanford University Press. s. 310–. ISBN 978-0-8047-5365-4.

- ^ Jamil Hilal (4. juli 2013). Where Now for Palestine?: The Demise of the Two-State Solution. Zed Books Ltd. s. 21–. ISBN 978-1-84813-801-8.

- ^ Maximum Jews, Minimum Palestinians: Ehud Olmert speaks out: Israel must espouse unilateral separation – withdrawal to lines of its own choosing. It's the only answer to the demographic danger, says this latter-day realist., 13.11.2003

- ^ FMA, "Address by PM Ariel Sharon at the Fourth Herzliya Conference" Dec 18, 2003:

"We wish to speedily advance implementation of the Roadmap towards quiet and a genuine peace. We hope that the Palestinian Authority will carry out its part. However, if in a few months the Palestinians still continue to disregard their part in implementing the Roadmap then Israel will initiate the unilateral security step of disengagement from the Palestinians." - ^ Exchange of letters between PM Sharon and President Bush. MFA, April 14, 2004

- ^ Ari Shavit (2004). "Top PM aide: Gaza plan aims to freeze the peace process". Haaretz.

- ^ Ali Abunimah (21. august 2007). One Country: A Bold Proposal to End the Israeli-Palestinian Impasse. Henry Holt and Company. s. 61–. ISBN 978-1-4299-3684-2.

In August 2005, for the first time since Israel was established, Jews no longer formed an absolute majority in the territory they controlled. Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics counted 5.26 million Jews living in Israel-Palestine and, combined with figures from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, there were 5.62 million non-Jews. Israel's pullout from the Gaza Strip allowed it to "subtract" the 1.4 million Palestinians who live there and claim therefore that the overall Jewish majority is back up to about 57 percent.

- ^ Ilan Peleg; Dov Waxman (6. juni 2011). Israel's Palestinians: The Conflict Within. Cambridge University Press. s. 122–. ISBN 978-0-521-76683-8.

The so-called demographic threat to Israel's ability to remain a Jewish and democratic state has become a major political issue in Israel over the past decade (this threat pertains not only to the Arab minority within Israel but also to Palestinians in the Occupied Territories over whom Israel effectively rules). It was one of the primary justifications used in support of Israel's unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip in August 2005, as Prime Minister Sharon presented the Gaza disengagement as a means of preserving a Jewish majority in the state. It was also the major rationale behind the short-lived "convergence plan" proposed in early 2006 by Sharon's successor Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, which would have involved a unilateral Israeli withdrawal from much of the West Bank. Both of these plans were intended, at least in part, to substantially reduce the number of Palestinians living under Israeli control. As such, they reflected the importance that demographic concerns had come to play in Israel. In the words of Shlomo Brom, a former Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Affairs and head of Strategic Planning in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF): “The most salient development in Israeli national security thinking in recent years has been the growing role of demography at the expense of geography.”

- ^ Paul Morland (23. maj 2016). Demographic Engineering: Population Strategies in Ethnic Conflict. Routledge. s. 132–. ISBN 978-1-317-15292-7.

Unlike the cases of Sri Lanka and Northern Ireland, the conflict in Israel/Palestine is unambiguously unresolved. Nor are the borders between Israel and a future Palestinian state agreed, if such a state ever comes into being. Yet those borders have been subject to considerable negotiation, discussion and, in the case of the barrier and Gaza withdrawal, of action. Only when the boundaries are finally drawn will we be able to determine whether a form of soft demography of the political/ethnic variety has been at work. Significant and concrete developments to date – namely the barrier and the Gaza withdrawal – have indeed been heavily influenced by demographic considerations and can therefore be considered as soft demographic engineering of an ethnic and political nature. For the time being however, this demographic engineering is work in progress.

- ^ Jerusalem Post, "In fact, the impetus for the pull-out has been attributed, at least in part, to Soffer's decades-long doomsaying about the danger the Palestinian womb posed to Israeli democracy."

- ^ August 15, 2005, Sharon's speech on Gaza pullout

- ^ a b Cook 2006, s. 104.

- ^ Abdel Monem Said Aly; Shai Feldman (28. november 2013). Arabs and Israelis: Conflict and Peacemaking in the Middle East. Macmillan International Higher Education. s. 373. ISBN 978-1-137-29084-7.

Far from seeing themselves as having withdrawn from Gaza in the summer of 2005 “under fire,” mainstream Israelis viewed their disengagement from the area as consequence of their success in abating the Intifada and, at the same time, their growing recognition of the limits of force. For them, by 2005 Israel was threatened not by violence but rather by demographic trends in the population residing between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River: changes in the relative size of population groups that now appeared to pose an enormous challenge to Israel’s future as a Jewish and democratic state. Since Jews were about to lose their majority status in the area, it became clear that Israel's continued control of Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem posed the following dilemma: either grant the Arab population in these areas full participatory rights, in which case Israel would lose its character as a Jewish state, or continue to deny them such rights, in which case Israel could no longer be considered a democracy.

(Webside ikke længere tilgængelig) - ^ Rynhold & Waxman 2008, s. 27.

Bibliografi[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

- Rynhold, Jonathan; Waxman, Dov (2008). "Ideological Change and Israel's Disengagement from Gaza". Political Science Quarterly. 123 (1): 11-37. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2008.tb00615.x. JSTOR 20202970.has

- Cook, Jonathan (2006). Blood and Religion: The Unmasking of the Jewish and Democratic State. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2555-2.

Eksterne links[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

Officielle dokumenter[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

- Kabinetsbeslutningen vedrørende tilbagetrækningsplanen, revideret tilbagetrækningsplan – hovedprincipper. Israel MFA, 6. juni 2004

- Premierminister Sharons erklæring om dagen for implementeringen af tilbagetrækningsplanen fra den israelske premierministers kontor

- Israels tilbagetrækningsplan: Fornyelse af fredsprocessen Officiel hjemmeside fra det israelske udenrigsministerium.

- Jan 2005.htm Israels frigørelsesplan: Udvalgte dokumenter Officiel hjemmeside fra det israelske udenrigsministerium.

- Ariel Sharons disengagement Plan og præsident Bushs brev, der accepterer den på MidEastWeb for Coexistence

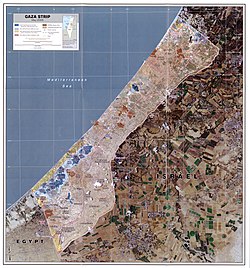

- Kort over tilbagetrækningsplan, der viser bosættelser, der skal evakueres på MidEastWeb for Coexistence

- Kort