Liepāja

Liepāja | |

|---|---|

State city | |

Aerial view | |

|

| |

| Anthem: Pilsētā, kurā piedzimst vējš "The City where the Wind is Born" | |

| Coordinates: 56°30′42″N 21°00′50″E / 56.51167°N 21.01389°E | |

| Country | |

| Town rights | 1625 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Gunārs Ansiņš (Liepājas partija) |

| Area | |

| • State city | 68.02 km2 (26.26 sq mi) |

| • Land | 51.33 km2 (19.82 sq mi) |

| • Water | 16.69 km2 (6.44 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 14 m (46 ft) |

| Population (2023)[2] | |

| • State city | 67,088 |

| • Density | 990/km2 (2,600/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 100,724 (with South Kurzeme Municipality) |

| GDP | |

| • State city | €1.052 billion (2021) |

| • Per capita | €15,700 (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | LV-34(01-13); LV-3414; LV-34(16–17) |

| Calling code | +371 634 |

| Number of city council members | 15 |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | www |

Liepāja (pronounced [liepaːja] ⓘ) is a state city in western Latvia, located on the Baltic Sea. It is the largest city in the Kurzeme Region and the third-largest in the country after Riga and Daugavpils. It is an important ice-free port.

In the 19th and early 20th century, it was a favourite place for sea-bathers and travellers, with the town boasting a fine park, many pretty gardens and a theatre.[4] Liepāja is however known throughout Latvia as the "City where the wind is born", likely because of the constant sea breeze. A song of the same name (Latvian: "Pilsētā, kurā piedzimst vējš") was composed by Imants Kalniņš and has become the anthem of the city. Its reputation as the windiest city in Latvia was strengthened with the construction of the largest wind farm in the nation (33 Enercon wind turbines) nearby.

Liepāja is chosen as the European Capital of Culture in 2027.[5]

Names and toponymy[edit]

The name is derived from the Livonian word Liiv, which means "sand". The oldest written text mentioning Līva village (Villa Liva) is a treaty between the bishop of Courland and the master of the Livonian Order dated 4 April 1253. In 1263, the Teutonic Order established a town which they called Libau in German and this was used until 1920. The Lettish name Liepāja was mentioned for the first time in 1649 by Paul Einhorn in his work Historia Lettica. A Russian name in Cyrillic from the time of the Russian Empire was Либава[6] (Libava) or Либау (Libau), although Лиепая (Liepaya), a transliteration of Liepāja, has been used since World War II.

Some other names for the city include Liepoja in Lithuanian,[6] the nearest neighbour, and Libow in English.[7]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

It is said that the original settlement at the location of modern Liepāja was founded by Curonian fishermen from Piemare as Līva, but Henry of Livonia (Henricus de Lettis), in his famous Chronicle, makes no mention of the settlement. The Teutonic Order established a village which they called Libau here in 1263, followed by Mitau two years later. In 1418 the village was sacked and burned by the Lithuanians.[citation needed][8]

Livonian confederation[edit]

During the 15th century, a part of the trade route from Amsterdam to Moscow passed through Līva, where it was known as the "white road to Lyva portus". By 1520 the river Līva had become too shallow for easy navigation, and development of the city declined.

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia[edit]

In 1560, Gotthard Kettler, first Duke of Courland and Semigallia, loaned all the Grobiņa district, including Libau, to Albert, Duke of Prussia for 50,000 guldens. Only in 1609 after the marriage of Sofie Hohenzollern, Princess of Prussia, to Wilhelm Kettler did the territory return to the Duchy. During the Livonian War, Libau was attacked and burnt by the Swedes.

In 1625, Duke Friedrich Kettler of Courland granted the town city rights, which were affirmed by King Sigismund III of Poland in 1626, although under what legal authority Sigismund had is debatable. Under Duke Jacob Kettler (1642–1681), Libau became one of the main ports of Courland as it reached the height of its prosperity. In 1637 Couronian colonization was started from the ports of Libau and Ventspils (Windau). Kettler was an eager proponent of mercantilist ideas. Metalworking and ship building became much more developed, and trading relations developed not only with nearby countries but also with Britain, France, the Netherlands and Portugal.

In 1697–1703, a canal was cut to the sea and a more modern port was built.[9] In 1701, during the Great Northern War, Libau was captured by Charles XII of Sweden, but by the end of the war, the city had returned to titular Polish possession.[10] In 1710 an epidemic of plague killed about a third of the population. In 1780 the first Freemasonry lodge, "Libanons", was established by Provincial Grand Master Ivan Yelagin on behalf of the Provincial Lodge of Russia; it was registered as number 524 in the Grand Lodge of England.[11]

Russian Empire[edit]

Courland passed to the control of the Russian Empire in 1795 during the third Partition of Poland and was organized as the Courland Governorate of Russia. Growth during the nineteenth century was rapid. During the Crimean War, when the British Royal Navy was blockading Russian Baltic ports, the busy yet still unfortified port of Libau was briefly captured on 17 May 1854 without a shot being fired, by a landing party of 110 men from HMS Conflict and HMS Amphion.[13]

In 1857, an Imperial Decree provided for a new railway to Libau.[14] That year the engineer Jan Heidatel developed a project to reconstruct the port. In 1861–1868 the project was realized – including the building of a lighthouse and breakwaters. Between 1877 and 1882 the political and literary weekly newspaper Liepājas Pastnieks was published – the first Latvian language newspaper in Libau.[15] In the 1870s the further rapid development of Russian railways, especially the 1871 opening of the Libava-Kaunas and the 1876 Liepāja–Romny Railways, ensured that a large proportion of central Russian trade passed through Libau.[16] By 1900, 7% of Russian exports were passing through Libau. The city became a major port of the Russian Empire on the Baltic Sea, as well as a popular resort. During this time of economic expansion, the city architect Paul Max Bertschy provided the design for many of the city's both public and private buildings, making an imprint on the architecture which can still be seen today.[17]

On the orders of Alexander III, Libau was fortified against possible German attacks. Fortifications were subsequently built around the city, and in the early 20th century, a major military base was established on the northern edge. It included formidable coastal fortifications and extensive quarters for military personnel. As part of the military development, a separate port was excavated exclusively for military use. This area became known as Kara Osta (War Port) and served military needs throughout the twentieth century.

Early in the twentieth century, the port of Libau became a central point of embarkation for immigrants travelling to the United States and Canada. By 1906 the direct ship service to the United States was used by 40,000 migrants per year. Simultaneously, the first Russian training school of submarine navigation was founded. In 1912 one of the first water aerodromes in Russia was opened in Libau.[18] In 1913, 1,738 ships entered Libau, with 1,548,119 tonnes of cargo passing through the port. The population had increased from 10,000 to over 100,000 within about 60 years.

World War I and War of Independence[edit]

Following the outbreak of World War I, the German cruiser SMS Magdeburg shelled Libau (then part of Russia), and other vessels laid mines off the approaches to the port.[19] Libau was occupied by the German Army, on 7 May 1915, and in memory of this event, a monument was constructed on Kūrmājas Prospect in 1916 and removed in 1919 by the new Latvian State. Libau's local government issued its own money for a while in this period – Libaua rubles. An advanced German Zeppelin base was constructed at Vaiņode, near Libau, with five hangars, in August 1915.[20] On 23 October 1915, the German cruiser SMS Prinz Adalbert was sunk by the British submarine HMS E8, 37 km (20 nmi; 23 mi) west of Libau.

With the collapse of Russia and the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the occupying German forces had a quiet time, but the subsequent defeat in the West of the German Empire and the Allied denunciation of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty changed everything. Independence of the Republic of Latvia was proclaimed on 18 November 1918, and the Latvian Provisional Government under Kārlis Ulmanis was created. Bolshevik Russia now advanced into Latvian territory and met little resistance here. Soon the Provisional Government and remaining German units were forced to leave Riga and retreated all the way to Libau, but then the Red offensive stalled along the Venta river. The Bolsheviks announced a Latvian Soviet Republic. Latvia now became the main theatre of Baltic operations for the remaining German forces in 1919. In addition, a Landeswehr was formed to work in conjunction with the German forces.

In Libau, a coup organized by Germans took place on 16 April 1919 and Ulmanis government was forced to flee and was replaced by Andrievs Niedra.[21] The Ulmanis government found shelter on the steamship "Saratov" in Libau port. In May a British cruiser squadron arrived at Libau to support Latvian independence and requested the Germans to leave.[22]

During the war, the words of "The Jäger March" were written in Libau by Heikki Nurmio.

The German Freikorps, having recaptured Riga from the Bolsheviks, departed in late 1919 and the Bolsheviks were driven out of the Latvian hinterlands in early 1920.

1920–1940[edit]

During the interwar period, Liepāja was the second major city in Latvia. In an attempt to put Libau 'on the map', on 31 January 1922, the Libau Bank was founded with significant new capital, transforming the old Libau Exchange Bank which had belonged to the Libau Exchange Association, and it eventually became the fourth-largest of Latvia's joint stock banks. However, when a Riga branch of the bank was opened, the business centre of gravity shifted from Liepāja so that by 1923 its Riga 'branch' was responsible for 90% of the turnover. The German consul in Liepāja reported at the time that "Riga, the economic heart of the country, draws all business to itself." The Latvian government ignored the pleas of the Libau Exchange Association to frustrate this.[23] In 1935 KOD (Latvian: Kara ostas darbnīcas) started to manufacture the light aircraft KOD-1 and KOD-2 at Liepāja. However it became evident in this year that trade with the new Soviet Union had virtually collapsed.[24]

World War II[edit]

The ports and human capital of Liepāja and Ventspils were targets of Joseph Stalin. He signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact in part to gain control of this territory. When the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Latvia in 1940, it nationalized private property. Many thousands of former owners were arrested and deported to the gulag camps in Siberia.

In 1941, Liepāja was among the first cities captured by the 291st Infantry Division of Army Group North after Nazi Germany began Operation Barbarossa, its war against the Soviet Union. German Nazis and Latvian collaborators virtually exterminated the local Jewish population, which had numbered about 7,000 before the war. Film footage of an Einsatzgruppen execution of local Jews was taken in Liepāja.[25][26] Most of these mass murders took place in the dunes of Šķēde north of the city. Fewer than thirty Jews survived in Liepāja by the end of the war.

One of the very few surviving films documenting the mass murder of Jews during the first stages of the Holocaust is a short film by a German soldier who witnessed the massacres of Liepāja Jews in July 1941 near the city's lighthouse.[26]

During the war, the German navy's U-boat crews received their torpedo training at Liepāja.

During the period of 1944–1945, as the Soviet Union began its offensive to the Baltic Sea, Liepāja was within the "Courland Pocket". It was occupied by the Red Army on 9 May 1945. Thousands of Latvians fled as refugees to Germany. The city had been devastated during the war, and most of the buildings and industrial plant were destroyed.

Latvian SSR[edit]

On 25–29 March 1949, the Soviet Union organized a second mass deportation to Siberia from Liepāja. In 1950 a monument to Stalin was erected on Station square (Latvian: Stacijas laukums). It was dismantled in 1958 after the Party Congress that discussed his abuses.

During 1953–1957, the city center was reconstructed under the direction of architects A. Kruglov and M. Žagare.[9] In 1952–1955 the Liepāja Academy of Pedagogy building was constructed under the direction of A. Aivars. In 1960 the Kurzeme shopping centre was opened. During the Soviet administration, Liepāja was a closed city; even local farmers and villagers needed a special permit to enter it.

The Soviet military set up its Baltic naval base and nuclear weapon warehouses there; The Beberliņš sandpit was dug out to extract sand used for constructing underground warehouses. In 1967 the Soviets completely closed the port to commercial traffic. One-third of the city was taken up with a Soviet naval base; its military staff numbered 26,000. The 14th Submarine Squadron of the USSR's Baltic Fleet (14 эскадрилья ЛиВМБ ДКБФ, call sign "Комплекс") was stationed there with 16 submarines (Types: 613, 629a, 651); as was the 6th group of Rear Supply of the Baltic Fleet, and the 81st Design Bureau and Reserve Command Center of the same force.

In 1977, Liepāja was awarded the Order of the October Revolution for heroic defense against Nazi Germany in 1941. Five residents were awarded the honorary title Hero of Socialist Labor: Anatolijs Filatkins, Artūrs Fridrihsons, Voldemārs Lazdups, Valentins Šuvajevs and Otīlija Žagata. Because of the rapid growth of the city's population, a shortage of apartment houses resulted. To resolve this, the Soviet government organized development of most of the modern Liepāja districts: Dienvidrietumi, Ezerkrasts, Ziemeļu priekšpilsēta, Zaļā birze and Tosmare. The majority of these blocks were constructed of ferro-concrete panels in standard projects designed by the state Latgyprogorstroy Institute (Латгипрогорстрой). In 1986 the new central city hospital in Zaļa birze was opened.[27]

1990–present[edit]

After Latvia regained independence after the fall of the Soviet Union, Liepāja has worked hard to change from a military city into a modern port city (again appearing on European maps after the secrecy of the Soviet period). The commercial port was re-opened in 1991, and in 1994 the last Russian troops left Liepāja. Since then, Liepāja has engaged in international co-operation, has been associated with 10 twin and partner cities, and is an active partner in several co-operation networks. Facilities are being improved. The city is the location of Latvia's largest naval flotilla, the largest warehouses of ammunition and weapons in the Baltic states, and the main supply centre of the Latvian army.

The former closed military town has been transformed into the northern neighbourhood of Karosta, occupying a third of the area of the city of Liepāja and attracting tourists to the remains of the military era.[28]

At the beginning of the 21st century, many ambitious construction projects were planned for the city, including a NATO military base,[29] and Baltic Sea Park, planned as the biggest amusement park in the Baltic states. Most of the projects have not yet been realised due to economic and political factors. Liepāja's heating network was renovated with the cooperation of French and Russian companies: Dalkia and Gazprom, respectively. In 2006, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands, a direct descendant of Jacob Kettler visited Liepāja. In 2010 the coal cogeneration 400 MW power plant was built in Liepāja with the support of the government.

Geography[edit]

Liepāja is situated on the coast of the Baltic Sea in the south-western part of Latvia. The westernmost geographical point of Latvia is located approximately 15 km (9 mi) to the south thus making Liepāja Latvia's furthest west city. The city occupies a 1.5-6.5 km wide coastal dune embankment and a foothill plain in the Bartau Plain of the Seaside Lowland. Liepāja is surrounded by the Dienvidkurzeme Region, and is bordered to the north by Medze Parish, to the east by Grobiņa Parish, and to the south by Nīca Parish, with its western border following the Baltic Sea coast. The Trade Channel (Tirdzniecības kanāls) connects the lake to the sea dividing the city into southern and northern parts, which are often referred to as Vecliepāja (Old Town) and Jaunliepāja (New Town) respectively. Along the coast, the city extends northwards until it reaches the Karosta Channel (Karostas kanāls). North of the Karosta Channel is an area called Karosta which is now fully integrated into Liepāja and is the northernmost district of the city. Liepāja's coastline consists of an unbroken sandy beach and dunes. Natural areas cover about one third of the territory of the city. These areas are mostly located on the outskirts of the city and are not connected to the small green areas in the central part of the city.[30][31]

Forests[edit]

Liepāja's urban forest covers 1368.9 ha, of which 83% are forest stands, the rest is covered by swamps (4.7%), meadows and sandhills (9.5%), flood plains and infrastructure sites (less than 3% in total). Private landowners own 109.6 ha, while 92% of the forest land area, or 1259.3 ha, belongs to the municipality. The urban forest consists of five separate forest massifs: the largest one is in the northern part of the city – the Karosta Forest. Other forests include Reiņu Forest, the forests near the regional hospital, the south-western forest and the Zaļā birze Forest. The city is characterised by a wide variety of forest growth types, determined and influenced by the geological and hydrological conditions of the area. Dry forests cover 39% of the forest area, forests on wet mineral soils 13%, swamp forests 22% and drained forests 26%.[31]

Surface waters[edit]

The water areas cover 1009 ha (17% of the total area of the city). The hydrological system of the City of Liepāja consists of various elements, including the Liepāja and Tosmare Lakes, which border the city to the east and are Natura 2000 sites (a quarter of the lake is located in the city, the rest is located in the Otanķi and Nīca municipalities). There are also rivers – the Vērnieku River, Kalējupīte and Ālande, canals: Tirdzniecības, Karostas, Cietokšņa and Pērkones (former river), as well as the artificial reservoir Beberliņi. The city is located on the Baltic Sea coast. According to the Latvian classification of river basin districts, the territory of the city of Liepāja falls within the Venta river basin district.[31]

Soils[edit]

The prevailing soil type and the prevailing geographical landscape of the area are determined by the low-fertility sandy loams and difficult natural drainage conditions characteristic of the Seaside Lowland. In terms of mechanical composition, sandy soils predominate, with typical podzols in the uplands and peaty podzolic gley vegetation in the depressions, as well as turf gley vegetation and turf podzolic gley vegetation. Due to the high humidity, the area is characterised by waterlogging.[31]

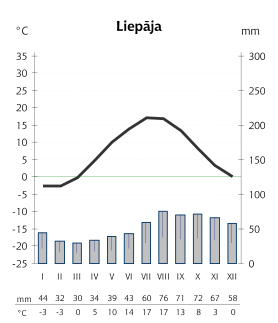

Climate[edit]

The climate in Liepāja is strongly influenced by the close proximity to the sea and is therefore located in the warm-summer humid continental climate zone noted as "Dfb" in the Köppen classification. The outflow of sea air creates relatively low summer and high winter temperatures for these latitudes. Liepāja has the highest average air temperature in Latvia at 7.0 °C (44.6 °F). In terms of hours of sunshine, Liepāja has one of the highest averages of 1940 hours of sunshine per year.[32] Winter is characterised by frequent thaws, so snow cover in the Seaside Lowlands is usually very patchy, rarely exceeding 5–10 cm in depth.[31] During the winter the sea around Liepāja is virtually ice-free. Although occasionally some land-fast ice may develop, it seldom reaches a hundred meters from the shore and does not last long before melting. The sea water usually reaches its summer maximum temperature at the beginning of August, while being less warm than, for example, in the Gulf of Riga due to the open sea. Winters are milder than inland areas to the east and comparable to the opposite coast on the Swedish mainland.

The number of windy days is high compared to inland areas of Latvia. The prevailing winds in the area tend to be all westerly and southerly. Their average speed is 6.1 m/s. Maximum wind speeds (greater than 20 m/s) are usually observed in autumn and winter, in most cases from the west. On 17–18 October 1967, the strongest storm in the history of the country occurred, and on 18 October the highest wind gust ever recorded in Latvia – 48 m/s – was recorded in Liepāja. The city has on average the most stormy days of the year – 7.9, when the average wind speed reaches 10.8 m/s. In 1971, this figure was as high as 36 days. The long-term trends indicate a very significant decrease in the number of stormy days.[33]

| Climate data for Liepāja (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1895–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

30.2 (86.4) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.7 (92.7) |

35.6 (96.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 5.7 (42.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.2 (82.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

1.2 (34.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.9 (30.4) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −14.8 (5.4) |

−13.2 (8.2) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−10.2 (13.6) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.9 (−27.2) |

−31.6 (−24.9) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−32.9 (−27.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 57.8 (2.28) |

41.9 (1.65) |

37.4 (1.47) |

28.6 (1.13) |

37.5 (1.48) |

50.7 (2.00) |

64.3 (2.53) |

76.3 (3.00) |

74.1 (2.92) |

84.2 (3.31) |

72.7 (2.86) |

67.5 (2.66) |

693.0 (27.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0mm) | 13 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 115 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87.5 | 86.2 | 82.5 | 76.2 | 75.1 | 78.4 | 78.3 | 78.2 | 80.7 | 83.1 | 86.9 | 87.2 | 81.7 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−3 (27) |

−2 (28) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

10 (50) |

14 (57) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

6 (43) |

2 (36) |

−1 (30) |

5 (40) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 41.6 | 71.1 | 148.5 | 223.7 | 300.1 | 302.4 | 309.4 | 264.7 | 187.9 | 113.1 | 40.9 | 25.7 | 2,029.1 |

| Source 1: Latvian Environment, Geology and Meteorology Centre[34][35] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation days, humidity 1991-2020),[36] Time and Date (dewpoints, 1985–2015)[37] | |||||||||||||

| Coastal temperature data for Liepāja | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.20) |

2.9 (37.22) |

3.5 (38.30) |

5.8 (42.44) |

10.1 (50.18) |

15.4 (59.72) |

19.7 (67.46) |

20.0 (68.00) |

16.5 (61.70) |

12.9 (55.22) |

10.3 (50.54) |

6.5 (43.70) |

10.6 (51.14) |

| Source 1: Seatemperature.net[38] | |||||||||||||

Closest cities[edit]

The closest city to Liepāja is Grobiņa, located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away towards Riga. Other main cities in the region are Klaipėda (approx. 110 km (68 mi) to the south), Ventspils (approx. 115 km (71 mi) to the north) and Saldus (approx. 100 km (62 mi) to the east). The distance to Riga (the capital of Latvia) is about 200 km (124 mi) to the east. The nearest point to Liepāja across the Baltic sea is the Swedish island of Gotland approximately 160 km (99 mi) to the north-west. The distance to Stockholm is 216 nautical miles. The closest major airports to Liepāja are Palanga International Airport – 60 km (37 mi) and Riga International Airport – 210 km (130 mi).

Architecture[edit]

Liepāja's architecture features buildings from different centuries: classical wooden buildings from the 17th century, highly regarded brick architecture, Eclecticism and Art Nouveau buildings at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as some buildings of the interwar period, Soviet-era functionalism and contemporary architecture. Many buildings were destroyed during World War II, which resulted in the destruction of almost the entire city built-up area between the Trade Canal and the Rose Square – more than 100 buildings. The development of Liepāja was entirely determined by economic conditions – initially the establishment of the port, and later, from the late 19th century, the expansion of industry.[39]

Early architecture[edit]

Liepāja reached its first period of construction and architectural prosperity in the 17th and 18th centuries. The development of the architecture and artistic styles of the buildings was reflected in the houses of the wealthier inhabitants, where Mannerism, Baroque, Classicism and other styles can be found. The common people built their homes using traditional building methods typical of the countryside.[40] The oldest type of building in Liepāja is a wooden log house on a low stone plinth with a steep tiled roof. This type of building can be found on Kungu Street, which was the main street of the town in the 17th century.[41] The building on 24 Kungu Street is notable for the visit of Tsar Peter I of Russia in 1697, while the neighbouring building on 26 Kungu Street was visited by King Charles XII of Sweden in 1700.[42] Other notable buildings are those at 6 Lielā Street, 3 Kungu Street, 13 Stendera Street, and the warehouses at 1 and 2 Jāņa Street and 4/6 and 10/12 Zivju Street.[39] After several unsuccessful attempts to build a harbour during the previous century, the Trade Canal was dug in 1703, which contributed to the growth of the city. At this time, the port warehouses were built out of wood, characterised by a high plinth created as a semi-basement. Most of the older warehouses were concentrated in Jūras Street, one of which was moved to the Open-Air Museum in the 1930s, while the others have not survived. Residential buildings in the harbour area were very small and densely distributed.[42] In 1848 there were 664 buildings in the town, of which only 46 were stone-built. Although wooden buildings were constructed, the most luxurious were built with roof extensions and ornate doors, panelling and beautifully painted pot stoves. The most ornate building in 18th century Liepāja was the Holy Trinity Cathedral[39]

Bertchy[edit]

With the construction of the Grobiņa highway in 1841 and the Liepāja-Romny railway in the 1870s, the city took on a different character. This was further marked by the appointment of Paul Max Bertchy as the city's first architect in 1871. The houses built by Bertchy form the most notable part of Liepāja's historic buildings. The wide range of Bertchy's diverse works includes the oil extraction plant and linoleum factory, mansions at 14 and 16 Krišjāņa Valdemāra Street, 15 Peldu Street, tenement houses on 44 Peldu Street, the Peldu Institution (bath house) in Jūrmala Park, the hospital complex on Dārtas Street, the gymnasium building at 4 Krišjāņa Valdemāra Street, the café at 2 Krišjāņa Valdemāra Street, the St. Anne's Church, the Rome Hotel and others. His red brick buildings are also well known. The architecture of this period uses high-quality woodwork, such as doors. The painted staircases are remarkable, not only in the luxurious houses, but also in the workers' tenements on 6 Palmu Street, 9 Avotu Street, 28 Republikas Street and 21 Kuršu Street.[39]

Art Nouveau[edit]

Liepāja is home to examples of the Art Nouveau style of architecture on a European scale. There are dozens of Art Nouveau buildings in the city, which in absolute numbers is more than in other European cities. Graudu Street is almost entirely defined by Art Nouveau along its entire length.[43] Most of the buildings are built in the restrained and laconic style of Northern National Romanticism.[44] Paul Max Bertchy designed several Art Nouveau buildings, but also significant are those by Theodor Max Bertchy (Bertchy junior), Ludwig Melville, Charles Carr, Lars Sonke, Pauls Kampe, Adolf Kucner, Gustav Janicek, William Losow, Max Kuhn, Alexander Zehrensen and Vasily Kosyakov. The Art Nouveau in Liepāja reflects mostly Latvian – German and partly also Russian as well as other interchanges.[45]

The most outstanding examples of Art Nouveau are the buildings on 2/6 Kūrmājas Prospect, 9 Ausekļa Street, 28, 34, 36/38, 44, 46, 27/29 and 45 Graudu Street, 3, 9, 16 and 23 Dzintaru Street, 8 Krišjāņa Barona Street, 23 Liepu Street, 33/35 Peldu Street, 1 and 11 Pasta Street, 4 and 5 Lielā Street, 2 Teātra Street, 18 Baznīcas Street, 21A Bāriņu Street, 22 Tirgoņu Street, 1, 5, 17 and 21 Kuršu Street, 8/10 and 16 Rožu Street, 6 Alejas Street (yard), 43 Toma Street, 11 Dīķa Street, 4 and 11 Avotu Street, 19 and 28 Republikas Street, 5, 13, 15/17, 19, 25 and 66 Uliha Street, 1 Raiņa Street, 10/12 Kroņu Street etc.[43]

Karosta[edit]

In the northern part of the city, under the guidance of the best Russian military architects and engineers, the Karosta complex was built, which was and is completely different from the rest of the city, both in function and in the character and traditions of its buildings. The Karosta is still an outstanding example of a militarised complex in Latvian architectural history. The district was built for the Russian army and is dominated by the Orthodox cathedral in the centre. The most important objects of the Karosta are the officers' meeting house and the residential complex, as well as the unique fortification system that encircled the entire city and connected the different parts of the city with underground passages. During World War I, the fortifications were partially blown up.[39]

Interwar period[edit]

During the interwar period, architect Jānis Blaus designed the project for the Latvian Society House in Liepāja. The building was erected in 1934 on the Rose Square. The Army Economic Store building was built in 1934–1935 according to the design of architect Aleksandrs Rācenis, but was destroyed during the Second World War. The pawnshop and savings bank building at 3 Teātra Street was built in 1936–1937.[40] During this period, the Friendly Vocation Primary School (now the 5th Secondary School; K. Bikše) and the Jaunliepāja Lutheran Church (K. E. Strandmann) were also built.[39]

Soviet era[edit]

Liepāja's city centre was devastated by the Second World War, and new development master plans were needed. The architecture and urban planning of Latvia, which was part of the USSR, was regulated by the uniform urban planning and building regulations of the Soviet Union. New centres for cities destroyed during the war were planned according to standardised formal principles – International Modernism, where streets had to be wide and squares regular, symmetrical, with a Lenin monument in the centre. Public buildings were designed to be representative – in line with Soviet architectural principles – large, spacious, imposing. In 1957, the building that now houses the University of Liepāja was built in a heavy eclectic style, designed by the architect Andrejs Aivars. An almost identical building is located in Daugavpils. The Kurzeme department store was built with large windows on the exterior walls and shop windows on the ground floor. During the Soviet period, the historical buildings of Liepāja's Old Town were eliminated over a wide area by the construction of a tram line from Kurzeme to Peldu Street. Changes also affected Lielā Street.[40] Due to the military port, Liepāja was a closed city, and thus construction in the city was rather slow until the 1970s, when the construction of new factories (Lauma, agricultural machinery factory, Hidrolats) and residential areas were built, the most important of which is the Ezerkrasts district.[39]

Contemporary architecture[edit]

After the restoration of independence, an artificial ice rink (architect U. Pīlēns), a Catholic monastery (A. Kokins) in Jaunliepāja, the "Māja" shop (reconstruction; A. Padēlis-Līns), new market pavilions in the city centre (U. Pīlēns) were built. The most remarkable building of the 21st century is the Great Amber Concert Hall. New-age construction is characterised by the use of new materials and technologies, as well as rationalism and functionalism.[39]

Monuments and memorials[edit]

Former monuments[edit]

Museums[edit]

|

Churches[edit]

Notable buildings[edit]

|

Administration[edit]

Fourteen deputies and a mayor make up the Liepāja City Council. City's voters select a new government every four years, in June. The Council selects from its members the Chairman of City Council (also called City Mayor), the two Vice chairmen (Deputy Mayors)

which are full-time positions. City Council also appoints the members of four standing committees, which prepare issues to be discussed in the Council meetings: Finance Committee; City Economy and Development Committee; Social Affairs, Health Care, Education and Public Order Committee; Culture and Sports Committee. The City of Liepāja had an operating budget of 104 million euros in 2022.[48] Traditionally, political leanings in Liepāja have been right-wing. In recent years the Liepāja Party has dominated the polls.

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1638 | 1,000 | — |

| 1800 | 4,500 | +350.0% |

| 1840 | 11,000 | +144.4% |

| 1881 | 29,600 | +169.1% |

| 1897 | 64,500 | +117.9% |

| 1907[49] | 81,000 | +25.6% |

| 1914 | 94,000 | +16.0% |

| 1921 | 51,600 | −45.1% |

| 1940 | 52,900 | +2.5% |

| 1950 | 64,200 | +21.4% |

| 1959[9] | 71,000 | +10.6% |

| 1970 | 92,900 | +30.8% |

| 1975[50] | 100,000 | +7.6% |

| 1989 | 114,500 | +14.5% |

| 1995 | 100,300 | −12.4% |

| 2000 | 89,100 | −11.2% |

| 2007 | 85,300 | −4.3% |

| 2011[51] | 83,400 | −2.2% |

| 2019[52] | 68,945 | −17.3% |

Liepāja's population structure has been multicultural and this impacted city's social life, economy and administration. Liepāja's population structure started to change after the abolition of serfdom in 1817. The number of inhabitants in 1800 is 4500, but in 1840 there already were 11 000 citizens. The number of city inhabitants has doubled in 40 years. It continued to grow and in 1881 Liepāja already had 29 600 inhabitants.[53] Liepāja's population grew fastest before World War I, almost tenfold in 50 years. It doubled during the 50 years of Soviet occupation, when population growth was hampered by the existence of the closed military port. Until World War I there was a high proportion of Baltic Germans, until World War II there was a high proportion of Jews, and during the Soviet occupation the number of Russians increased. The proportion of Latvians increased from 16% in 1863 to 85% in 1943 until World War II, but decreased again after the war.[39]

With 68,945 inhabitants in 2019, Liepāja is the third-largest city in Latvia. Its population has declined since the withdrawal of Soviet military forces; the last of which left in 1994. In addition, many ethnic Russians emigrated to Russia in 1991–2000. More recent causes include economic migration to Western European countries after Latvia joined the EU in 2004, and lower birth rates. The demographic situation in Liepāja is unfavourable, as the natural population growth is negative.[39] However, the trend of people leaving Liepāja is gradually decreasing, and in 2018 a positive migration balance was achieved for the first time in many years. Favourable migration trends are more and more significantly compensating for the negative natural increase, so the overall population decline trend has been significantly reversed in 2017 and 2018. The dependency load is 690 children, adolescents and pensioners per 1000 inhabitants, which is the highest value among the major cities.[54] The population decreased by an average of 750 inhabitants per year between 2012 and 2018.[55]

Religion[edit]

Liepāja has a number of churches. As elsewhere in central and western Latvia, Protestant churches, mostly Lutheran, are predominant. Holy Trinity Cathedral houses the seat of the Lutheran Bishop of Liepāja. Other Lutheran congregations are St. Anne, Church of the Cross and Church of Luther. There are four Baptist congregations in the city, among them are St. Paul church and Church of Zion.

Owing to the regional importance of Liepāja during the last decades of the Russian Empire, a number of Russian Orthodox churches were established in the city early in the twentieth century. Their congregations are chiefly drawn from the Russian-speaking population.

The Catholic faith is represented in Liepāja by a St. Joseph Cathedral – the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Liepāja, Catholic primary school and the Catholic centre. The structure of the Catholic centre was used to represent the Vatican in Expo 2000 in Hanover and was transferred to Liepāja after the event.

Other Christian sects include Old Ritualists, Adventist, Pentecostal, Latter-day Saints and Jehovah's Witnesses, who have single congregations and churches.

Economy[edit]

After the collapse of USSR's centrally planned economy, Liepāja had to deal with issues of rundown infrastructure. To provide business incubation and development for the city, Liepāja Special Economic Zone (Liepāja SEZ) was established. According to the law, Liepāja SEZ was established on March 1, 1997, and it will exist until December 31, 2035. The purpose of the Liepāja SEZ is to develop a business environment, manufacturing, shipping and air traffic, as well as international trade through Latvia. The aim of the Liepāja SEZ is to attract investment for expanding of manufacturing and infrastructure, and to create new work places and to ensure the development of the region. In the beginning, investment growth remained slow due to a shortage of a skilled labour force, but the scheme proved to be successful as positive tendencies can be seen with formation of new businesses.[53]

After joining the European Union in 2004, many companies were faced with strict European rules and tense competition. In 2007 Liepājas cukurfabrika and Liepājas sērkociņi closed down; Līvu alus, Liepājas maiznieks and Lauma have been sold to European investors. in 2013, the steel production company Liepājas Metalurgs went bankrupt, which was one of the largest economic disasters in modern Latvian history, costing the state around 230 million LVL (327 million EUR).[57][58] Today, the city's economic development is mainly driven by Liepāja Special Economic Zone, Trade Port and the companies placed there. In 2021, the companies in Liepāja with the largest turnover are TOLMETS, AE Partner, and Jensen Metal[59]

Transport[edit]

Liepāja's transport system consists of 31 bus lines (5 of which are connected to Grobiņa), as well as one Liepāja tram line, which is 7 kilometres long. The tram line was founded after the opening of the first Liepāja power plant in 1899, which makes it the oldest electric tram line in the Baltic states;[60] it is now operated by the municipal company Liepājas tramvajs. In 2013, the tram line was extended by 1.7 km from the Dienvidrietumu residential area (Klaipėda Street) to the Ezerkrasts residential area with a turnaround at the end of Mirdzas Ķempes Street. Liepāja has direct bus connections to Riga, Riga International Airport, Ventspils, Jelgava, Klaipėda and other destinations.

Liepāja has a railway connection to Jelgava and Riga and through them to the rest of Latvia's railway network. There is just one passenger station in the New Town, but the railway extends further and links to the port. There is also a northward railway track leading to Ventspils, but in recent decades it has fallen into disuse for economic reasons. The railway provides the main means of delivering cargo to the port. Two main highways, the A9 and A11, connect the city and its port to the rest of the country. The A9 leads north-west towards Riga and central Latvia and the A11 leads south to the border with Lithuania and its only port Klaipėda and to Palanga International Airport.[61] The city also hosts Liepāja International Airport, one of three international airports in Latvia; it is located outside the city limits, north of the Lake of Liepāja near Cimdenieki. However, as of 2020 the airport only serves private, military flights or flight training as the national carrier airBaltic no longer has any low capacity fleet to facilitate flights from the airport.[62]

The Port of Liepāja has a wide water area and consists of three main parts. The Winter harbour is located in the Trade channel and serves small local fishing vessels as well as medium cargo ships. Immediately north of the Trade channel is the main area of the port, separated from the open sea by a line of breakwaters. This part of the port can accommodate large ships and ferries. Further north is Karosta harbour, also called Karosta channel, which was formerly a military harbour but is now used for ship repairs and other commercial purposes. Liepāja also welcomes yachts and other leisure vessels which can enter the Trade channel and moor almost in the center of the city.

Education[edit]

History[edit]

The idea to open a school was born in 1560 during a church survey, and schools existed in Liepāja before 1625. However, it was the granting of city rights that encouraged the further development of schools, as the maintenance of schools was considered one of the city's responsibilities. Both German and Curonian children were encouraged to attend the newly founded school. It was announced to the "non-Germans" that those children who were sent to the school would be freed from all servitude and even freed from serfdom; they would also be given help for further education. At the beginning the school was a one-class school; the second class was opened in 1638; from 1650 the school had 3 classes, and in 1750 the 4th class was opened. In 1788 a new school building was built, and in 1806 the town school was transformed into the county's highest school after 250 years of existence. This county school was attended by Krišjānis Valdemārs and Kronvaldu Atis. In 1866, the county school was converted into the Nikolai Gymnasium. In 1861, a maritime class was opened at the county school, which was added to the Liepāja Maritime School in 1876. The first girls' high school was opened in 1871, and by 1874 there were already 2 girls' high schools, one of which was turned into a gymnasium in 1886. In the following years, the Russification of schools, which started with the law of 1889, turned all schools into Russian schools, however, there were schools attended by Latvian children in their majority, where Latvian was taught as a subject and religious studies were taught in Latvian. Schools with Latvian as the only language only appeared after Latvia gained independence.[63]

During the First Free State there were three secondary schools, 25 primary schools, two technical schools, a trade school, a secondary school of applied arts, a trade institute, a technical evening craft school, a Jewish craft school, a fishing and fish farming school. There was also a folk conservatory and various evening courses. In December 1919, a separate children's section was opened in the library – the first in Latvia.

After World War II, Liepāja was home to the Liepāja Pedagogical Institute (founded in 1954; in 1945 as the Pedagogical School, in 1950 as the Liepāja Teachers' Institute), the General Technical Faculty of the Riga Polytechnic Institute, a maritime school, a medical school, a polytechnic, the Liepāja Applied Arts High School (founded in 1926), a music school, ten comprehensive schools, two vocational-technical high schools and two technical schools.[39]

Today[edit]

Liepāja has wide educational resources. In March 2019, the Liepāja City Council decided to merge Secondary School No. 2 with Secondary School No. 12 to form a new secondary school, taking full advantage of the modernised learning environment of Secondary School No. 2,[64] In 2022, the city has 21 kindergartens, twelve general education institutions and two private schools, 2 music schools and two boarding schools providing education in the city's largest residential districts.[65] Interest education for children and youth is available in 8 municipal institutions: Children and Youth Centre, Youth Centre, Centre for Young Technicians, Art and Creation Centre "Vaduguns", Complex Sport School, Gymnastics School, Tennis Sports School, Sports School "Daugava" (football, track-and-field athletics) and Basketball Sports School. Liepāja Central Library has six branches and audio record library. Literature fund consists of about 460,000 copies and online catalogue.[66] Average annual number of visitors – 25000.

Liepāja also has several higher education institutions represented by[67]:.

- University of Liepāja

- Riga Technical University Liepāja branch

- Rīga Stradiņš University Liepāja branch

- Baltic International Academy Liepāja branch

- Turība University Liepāja branch

- Riga Technical College Liepāja branch

- College of Law Liepāja branch

- Liepāja Maritime College[68]

- Liepāja Medical College

- Liepāja Applied Art School

- Liepāja Carpentry School

- Liepāja Tourism and Textile Design School

Culture[edit]

Liepāja is known as a city rich in deep cultural and historical traditions, and has a very important place in the cultural landscape of Latvia and the region. Liepāja is home to both state and municipal institutions, as well as the University of Liepāja and privately funded artistic groups and departments. The city has a remarkable legacy in terms of its historical cultural environment, buildings, monuments, visual art collections, museums and libraries. Liepāja has a strong tradition of performing arts and intangible cultural heritage – crafts, folk art, traditional culture – in both Latvian and minority groups. Cultural tourism and creative industries are developing. There is a strong cultural education base (in its professional forms). Certain sectors are relatively underdeveloped in Liepāja (fine arts, literature, declining cinema, etc.).

Liepāja took part in the competition for the European Capital of Culture (ECOC) status in 2014, but on 15 September 2009 the European Commission jury recommended that Riga be awarded the status.[69] Having taken part in the competition for the European Capital of Culture status in 2027, on 10 May 2022 the jury awarded the status to Liepāja.[5]

Symbols[edit]

Liepāja has three officially approved symbols: a coat of arms, a flag and an anthem. The coat of arms was adopted four days after the jurisdiction gained city rights on 18 March 1625,[70] and the present version is introduced in 1925;[71] while the flag was first officially proclaimed in 1938 with the Law on the Flag of the City of Liepāja. The coat of arms of Liepāja is described as: "on a silver background, the lion of Courland with a divided tail, who leans upon a linden (Latvian: Liepa) tree with its forelegs". The flag of Liepāja has the coat of arms in the center, with red in the top half and green in the bottom.[70] The anthem The City where the Wind is Born (Pilsētā, kurā piedzimst vējš) was approved in 1999 and premiered in the first hour of 2000. Imants Kalniņš wrote the song "In the City where the Wind is Born" in 1973, dedicating it to Liepāja and the people of Liepāja, with lyrics by Māris Čaklais. It was first performed by Austra Pumpure, and even then the song gained the status of an unofficial anthem of Liepāja residents. Liepāja also has its own special dish – 'Liepājas menciņi' (smoked, dried cod with potatoes, onions and dill in heavy cream, fried in a ceramic pot), which is based on an ancient recipe from South Courland.[72] Dried, smoked or lightly dried codfish was used in the diet of the coastal inhabitants of Courland – Livonians and Curonians – even before the arrival of German settlers in the 13th century.

The use of Liepāja's symbols is regulated by the Binding Regulations adopted by the City Council on 25 February 1999.

Music[edit]

Liepāja is known as the music capital of Latvia. The Liepāja Symphony Orchestra, the oldest orchestra in the Baltic States, performs in Liepāja. It remains the only professional orchestra in Latvia outside Riga.[73] Liepāja is home to bands such as Līvi, Credo, 2xBBM and Tumsa, as well as composers such as Zigmars Liepiņš, Jānis Lūsēns and Uldis Marhilēvičs. Music festivals such as Summer Sound, International Star Festival, VIA Baltica Festival, International Organ Music Festival and others are organised.[55] From 1964 to 2006, Liepājas Dzintars, the longest-running and most tradition-rich popular music festival in Latvia, was held in the Pūt, vējiņi concert garden.[74]

Visual arts[edit]

Liepāja's art scene has a long and rich tradition. The oldest and most outstanding work of art in Liepāja is the altar of St Anne's Church, built in 1697. The most significant work of art of the 18th century is the organ of the Holy Trinity Cathedral The interior decoration of the Old Catholic Church is also noteworthy – ornamental formations in plaster (1762) and the altar retable – a typical late Baroque work, paintings of columns, walls and ceilings, stained glass windows. Works of applied art masters are in the Liepāja Museum. There are 18th-century door sashes from the house at 13 Stendera Street and works by tin foundrymen. The most outstanding sculpture of the 19th century is the sculpture by Fabiani for the chapel in the Old Cemetery, but the sculpture in the city is mainly memorial works. In the Northern Cemetery there is a monument to the memory of the soldiers who died in the Latvian War of Independence, there is also a memorial marker to Colonel Oskars Kalpaks at his first burial site, and in the Jewish burial section of the Līva Cemetery there is a monument to the memory of the Jewish soldiers who died in the Latvian War of Independence near Liepāja. In Jūrmala Park, there is a monument to the sailors and fishermen perished in the sea and to the 16 January 1905 rally. Nearby is a monument to the poet Mirdza Ķempe. Until the restoration of independence, the city had several monuments created during the Soviet occupation, of which the monument to the 1941 defenders of Liepāja remains in place,[39] but it is being dismantled in 2022.[75] Since 1996, the town has been decorated with memorial sculptures to the bed of the River Līva, created in a plenary workshop led by Ģirts Burvis. The Liepāja anthem "In the City where the Wind is Born" is reproduced in bronze sculptures along the entire length of Kūrmāja Prospect.[76] There is a rich tradition of painting.[39]

Theatre[edit]

In 1907 the Liepāja Latvian Dramatic Society was founded. Together with other societies, in March 1907 it established and maintained the Liepāja Latvian Theatre (now Liepāja Theatre), which is the oldest Latvian professional theatre still in existence. In 1918 the theatre moved to its present premises – the City Theatre on the then Hagedorna (now Teātra) Street.[77]

Sports[edit]

In 1998, the first ice hockey rink built in Latvia during the years of independence was opened in Liepāja which has since hosted regular ice hockey games including two youth World championship games. HK Liepājas Metalurgs became the home team of the Olympic Ice Arena. The team won eight Latvian championship gold medals, and also won the 2002 Eastern European Hockey League tournament. Due to problems at the metallurgical company, the hockey team ceased operations in the summer of 2013. In 2014, the HK Liepāja was founded and they became champions of the Latvian Hockey Higher League in 2015–16 season.

In January 2014, the FK Liepājas Metalurgs ceased operations and was replaced by the FK Liepāja, who became Latvian champions in 2015. Their home stadium is the Daugava Stadium. Liepāja is home to Latvian Basketball League club Betsafe/Liepāja.

On 2 August 2008, a new multipurpose sports arena – Liepāja Olympic Centre was officially opened. It has been established as one of the most modern multipurpose sports and cultural complexes in Latvia. Liepāja regularly hosts various sporting events, such as the World and European Basketball Championships, and the 2009 Women's European Basketball Championship Subgroup A and B matches were played at the Liepāja Olympic Centre. The European Rally Championship stage "Rally Liepāja", the International Windsurfing Competition and others are also held.[78]

Media[edit]

Liepāja has a regional newspaper Kurzemes vārds and a regional TV channel TV Kurzeme. The city also has several regional Internet portals; there is an amateur radio community[79] and a citywide wireless video monitoring system. As of 2010[update], digital terrestrial television is fully operational; mobile television and broadband wireless networks are implemented. All four Latvian mobile operators have stable zones of coverage (GSM 900/1800, UMTS, 2100 CDMA450) and client service centers in Liepāja.

Representation in other media[edit]

- In 1979 a part of the film Moonzund was filmed in the town.

Notable people[edit]

- Woldemar Kernig (1840—1917) — Russian and German neurologist;

- Reuven Dov Dessler (1863–1935) – rabbi;

- Miķelis Valters (1874—1968) — politician, first Latvian Minister of Interior;

- Lina Stern (1878—1968) — biochemist;

- Yanka Maur (1883—1971) — Belarusian writer;

- Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler (1892–1953) – rabbi;

- Augusts Annuss (1893—1984) — painter;

- Eduard Tisse (1897—1961) — cameraman;

- Leon Josephson (1898–1966) – American lawyer and Soviet spy;

- Jacob Klein (1899–1978) – Russian-American Jewish philosopher;

- Herberts Cukurs (1900—1965) — aviator and Nazi collaborator;

- Valdemārs Baumanis (1905—1992) — basketball coach;

- Balys Dvarionas (1905—1972) — Lithuanian composer;

- Stanisław Jaśkiewicz (1907—1980) — Polish actor;

- Mirdza Ķempe (1907—1974) — poet;

- Arvīds Jansons (1914—1984) — conductor, father of Mariss Jansons;

- Tālivaldis Ķeniņš (1919—2008) — composer;[80]

- Morris Halle (1923—2018) — Latvian-American Jewish linguist;

- Zvi Harry Hurwitz (1924—2008) — South African journalist, Israeli diplomat and adviser to two prime ministers

- Ernesto Foldats (1925—2003) — biologist;

- George D. Schwab (1931) — American political scientist, editor, Holocaust survivor, and academic;

- Kirovs Lipmans (1940) — businessman;

- Teofils Biķis (1950—2000) — pianist;

- Zigmars Liepiņš (1952) — composer:

- Jānis Vanags (1958) — Archbishop of Riga in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia;

- Laila Pakalniņa (1962) — film director;

- Igo (1962) — singer and composer;

- Mārtiņš Freimanis (1977—2011) — musician and actor;

- Konstantin Konstantinovs (1978—2018) — Latvian-Russian powerlifter;

- Māris Verpakovskis (1979) — football player;

- Romāns Miloslavskis (1983) — swimmer and politician;

- Mareks Mejeris (1991) – basketball player for Hapoel Jerusalem of the Israeli Basketball Premier League;

- Anastasija Sevastova (1990) — tennis player;

- Kristaps Porziņģis (1995) — basketball player;

- Rūdolfs Balcers (1997) — ice hockey player

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Nynäshamn, Sweden (1990)

Nynäshamn, Sweden (1990) Elbląg, Poland (1991)

Elbląg, Poland (1991) Bellevue, United States (1992)

Bellevue, United States (1992) Darmstadt, Germany (1993)

Darmstadt, Germany (1993) Klaipėda, Lithuania (1997)

Klaipėda, Lithuania (1997) Gdynia, Poland (1999)

Gdynia, Poland (1999) Årstad (Bergen), Norway (2001)

Årstad (Bergen), Norway (2001) Palanga, Lithuania (2001)

Palanga, Lithuania (2001) Helsingborg, Sweden (2005)

Helsingborg, Sweden (2005) Guldborgsund, Denmark

Guldborgsund, Denmark

Gallery[edit]

-

Pētertirgus

-

St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Naval Cathedral (1901–1903), architect Vasily Kosyakov

-

Church of St. Anna

-

Liepāja railway station

-

The ruins of the southern forts

-

St. Joseph church

-

Liepāja border marker.

See also[edit]

![]() Liepāja travel guide from Wikivoyage

Liepāja travel guide from Wikivoyage

References[edit]

- ^ "Reģionu, novadu, pilsētu un pagastu kopējā un sauszemes platība gada sākumā". Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "Iedzīvotāju skaits pēc tautības reģionos, pilsētās, novados, pagastos, apkaimēs un blīvi apdzīvotās teritorijās gada sākumā (pēc administratīvi teritoriālās reformas 2021. gadā) 2021 - 2022". Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ "Gross domestic product and gross value added by planning region, State city and municipality at current prices (after administrative-territorial reform in 2021)". stat.gov.lv.

- ^ Murray, John, Russia, Poland, and Finland, etc., Third Revised Edition, London, 1875, p.85.

- ^ a b "Liepāja wins the title of European Capital of Culture 2027". 10 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ a b "KNAB, the Place Names Database of EKI". Eki.ee. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ SAURUSAITIS, Peter P. "Thirty days in Lithuania in 1919: Being an account of personal experiences and observations encountered in a trip extending from August 30, 1919, to February 16, 1920". Project Gutenberg. p. 9. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen, Tannenberg 1410, Osprey Publishing, Oxford UK, 2003, p.82: Certainly Poland & Lithuania invaded Prussia again in 1422, but no mentions of Libau.

- ^ a b c "Лиепая". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Moscow: Советская Энциклопедия. 1969–1978. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ "Liepāja". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1997.

- ^ "Masonicum". masonicum.lv. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Žemaitis, Augustinas. "History of Liepāja". OnLatvia.com. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Colomb, Philip Howard. "Memoirs of Admiral the Right Honble. Sir Astley Cooper Key". ebooksread.com. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ Palmer, Alan, Northern Shores, London, 2005, p.215.

- ^ "Liepājas Pastnieks". Latvijas Enciklopēdiskā vārdnīca (in Latvian).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Либаво-Роменская железная дорога. Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1907. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Paul Max Bertschy". Visit Daugavpils. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Гидроаэродром. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). 1969–1978. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Palmer, 2005, p.255

- ^ Palmer, 2005, p.258.

- ^ Šiliņš, Jānis (18 April 2019). "The republic on the sea: The 1919 coup that exiled the Latvian government to a steamboat". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Hiden, John, and Salmon, Patrick, The Baltic Nations and Europe, Longman Group UK Ltd., 1991, p.32-6.

- ^ Hiden, John, The Baltic States and Weimar Ostpolitik, Cambridge University Press, UK, 1987, p.101-3.

- ^ Hiden & Salmon, 1991, p.78.

- ^ "Crimes of Einsatzgruppen in Liepāja". 1941. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b Mass murder of Jews in Liepaja (Yad Vashem channel, YouTube)

- ^ "Site of Liepājas slimnica" (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Liepāja Naval Port".

- ^ "Liepāja to host military base with NATO-standard docks". Lsm.lv. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Letonika.lv – Liepāja". 2002.

- ^ a b c d e SIA "GRUPA 93" (2012). "STRATĒĢISKAIS IETEKMES UZ VIDI NOVĒRTĒJUMS. Vides pārskats" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "4. Latvijas klimats un tā mainības raksturs". edu.lu.lv. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Avotniece, Zanita; Aņiskeviča, Svetlana; Maļinovskis, Edgars (2017). "KLIMATA PĀRMAIŅU SCENĀRIJI LATVIJAI. Ziņojums" (PDF).

- ^ "Klimatisko normu dati" (in Latvian). Latvian Environment, Geology and Meteorology Centre. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Gaisa temperatūras rekordi" (in Latvian). Latvian Environment, Geology and Meteorology Centre. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981-2010". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in Liepāja". Time and Date. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Liepāja Sea Temperature". seatemperature.net. 25 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Caune, Māra; K̦īsis, Aleksis (1999). Latvijas pilsētas : enciklopēdija. Riga. ISBN 9984-00-357-4. OCLC 50383143.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c dzejaprozamaterialiberniem (13 August 2017). "Liepājas arhitektūra gadsimtu griežos". Mani raksti (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Koka apbūve". Koka apbūve (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ a b Sāne-Alksne, Līga (1991). Ceļvedis Liepājas arhitektūrā (in Latvian). Liepāja: Liepājas pilsētas arhitektūras un pilsētbūvniecības pārvalde.

- ^ a b "Jūgendstils kā Liepājas arhitektūras īstā rota". building.lv (in Latvian). 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Jūgendstils". Jūgendstils (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Jānis Krastiņš Cosmopolitan Atmosphere and Latvian Jugendstil in Liepāja – PDF Free Download". docplayer.net. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Site of the Liepāja museum" (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Site of Karosta prison museum". karostascietums.lv. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Budžets 2022. gadam". Budžets 2022. gadam (in Latvian). Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Либава. Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). St. Peterburg: Брокгаузъ-Ефронъ. 1907. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Город родной на семи ветрах (in Russian). Liesma. 1976. p. 263.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "PASTĀVĪGO IEDZĪVOTĀJU NACIONĀLAIS SASTĀVS REĢIONOS UN REPUBLIKAS PILSĒTĀS GADA SĀKUMĀ". csb.gov.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Platība, iedzīvotāju blīvums un pastāvīgo iedzīvotāju skaits reģionos, republikas pilsētās un novados gada sākumā. Centrālās statistikas pārvaldes datubāzes. Retrieved 12 June 2017

- ^ a b Eglins-Eglitis, Atis; Lusena-Ezera, Inese (1 January 2016). "From Industrial City to the Creative City: Development Policy Challenges and Liepāja Case". Procedia Economics and Finance. 3rd Global Conference on Business, Economics, Management and Tourism. 39: 122–130. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(16)30256-8. ISSN 2212-5671.

- ^ "ESOŠĀS SITUĀCIJAS RAKSTUROJUMS LIEPĀJAS PILSĒTĀ – EKONOMIKA" (PDF).

- ^ a b "ESOŠĀS SITUĀCIJAS RAKSTUROJUMS LIEPĀJAS PILSĒTĀ – KULTŪRA" (PDF).

- ^ "Liepāja Northern Shipyard". Lzk.lv. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Liepājas metalurgs' bankruptcy to cost Latvia around LVL 230 million | Baltic News Network – News from Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia". 12 November 2013. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ курс, The Baltic Course-Балтийский. "Liepājas metalurgs bankruptcy – the greatest economic disaster since Parex collapse". The Baltic Course | Baltic States news & analytics. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Uzņēmumi ar lielāko apgrozījumu pa gadiem, Statistika Latvijas novadu/pilsētu griezumā, Liepāja, Latvijas rajoni un novadi, Lursoft statistika,Lursoft". statistika.lursoft.lv. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ catchsmartsolution.com, CatchSmart |. "Liepājas tramvajs" (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Noteikumi par valsts autoceļu un valsts autoceļu maršrutā ietverto pašvaldībām piederošo autoceļu posmu sarakstiem". 13 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "PAVAICĀ TVNET ŽURNĀLISTAM ⟩ Cik vēl ilgi Liepājas lidosta būs dīkstāvē?". TVNET (in Latvian). 27 September 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ "Liepājas 300 gadu jubilejas piemiņai, 1625-1925". 1925.

- ^ "Lēmums pieņemts. Apvienošanas process ir sācies". irliepaja.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Vispārizglītojošās skolas". Vispārizglītojošās skolas (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Catalog of Liepāja central library". liepajasczb.lv (in Latvian). Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Augstākā izglītība". Augstākā izglītība (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Liepājas Jūrniecības koledža". Ljk.lv. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission – European Commission. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Liepājas vēsture". liepaja.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ "Liepāja". Heraldry of the World. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ catchsmartsolution.com, CatchSmart |. "Liepājas īpašais ēdiens ar Kurzemes smeķi – "Liepājas menciņi"" (in Latvian). Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Liepājas simfoniskais orķestris". lso.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ ""Liepājas dzintars"". enciklopedija.lv. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Liepājā demontēs trīs padomju okupācijas laika pieminekļus". liepajniekiem.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ catchsmartsolution.com, CatchSmart |. "Liepājas himnas tēlu skulptūras" (in Latvian). Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Liepājas teātris :: Teātra iela 4, Vecliepāja, Liepāja, Kurzemes reģ. :: Vietas.lv". Vietas.lv – Latvijas ceļvedis, Latvijas karte, pilsētas, rajoni, tūrisma un citi interesanti objekti, pasākumi. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Par sporta dzīvi Liepājā". Par sporta dzīvi Liepājā (in Latvian). Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "Site of Liepājas radio amatieru grupa". lrg.lv. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Tālivaldis Ķeniņš Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, Latvijas Mūzikas informācijas centrs.

- ^ "Sadraudzības pilsētas". liepaja.lv (in Latvian). Liepāja. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Мелконов, Юрий (2005). Пушки Курляндского Берега. Riga, LV: GVARDS. ISBN 9984-19-772-7.

- Кондратенко, Р. В. (1997). "Военный порт Александра III в Лиепае". Saint-Peterburg, RU: Исторический альманах "Цитадель", No. 2(5), изд. "ОСТРОВ".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Вушкан, Янис Владиславович (1976). "Город родной на семи ветрах". Riga, LV: Liesma.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Tooms, Viljars (2003–2007). "Liepājnieku biogrāfiskā vārdnīca". Riga, LV: Tilde Letonika.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Sāne (Alksne), Līga (1991). "Ceļvedis Liepājas arhitektūrā". Liepāja, LV: Liepājas pilsētas TDP IK Arhitektūras un pilsētbūvniecības pārvalde.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Jāņa sēta. (2003). Liepājas pilsētas plāns. Riga, LV: Karšu izdevniecība Jāņa sēta. ISBN 9984-07-330-0.

- Gintners, Jānis (2004). "Liepājas gadsimti". Liepāja, LV: Liepājas muzejs.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Gintners, Jānis, Uļa (2008). Liepāja Latvijas sākotnē. Liepāja, LV: Liepājas muzejs. ISBN 978-9984-39-723-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gintnere, Uļa (2005). Liepāja laikmetu dzirnavās. Liepāja, LV: Kurzemes Vārds. ISBN 9984-9190-4-8.

- Lancmanis, Imants (1983). "Liepāja no baroka līdz klasicismam". Rīga, LV.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Liepājas 300 gadu jubilejas piemiņai: 1625–1925". Liepāja, LV. 1925.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Wegner, Alexander (1970) [1878]. Geschichte der Stadt Libau. Libau: v. Hirschheydt. ISBN 3-7777-0870-4.

- Tīre, Irina (2007). Liepāja in graphics. Latvia: Poligrāfijas infocentrs. ISBN 978-9984-764-92-4.

- Dorenskis, Jaroslavs (2007). "Liepājas Metalurgs: Anno 1882". Liepāja, LV: Fotoimidžs: 364.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Корклыш, С. (1966). Лиепая (in Russian). Rīga: Liesma.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Evans, Nicholas J. (2006). "The Port Jews of Libau, 1880–1914". In David Cesarani; Gemma Romain (eds.). Jews and Port Cities: 1590–1990: Commerce, Community and Cosmopolitanism. London, UK: Vallentine Mitchell & Co Ltd. pp. 197–214. ISBN 978-0-85303-681-4.

- Eberstein, Ivan H. The Amber Land: Libava's Tragic Fate and the Fall of the Russian Empire. New York.

External links[edit]

- www.liepaja.lv – Liepāja City Council official website

- History of Liepāja

- www.liepajniekiem.lv – Liepāja news in Latvian and Russian (in Latvian and Russian)

- www.portofliepaja.lv – Port of Liepāja

- www.orkestris-liepaja.lv – Liepāja Symphony orchestra

- Kurzemes Vārds – Liepāja regional newspaper (in Latvian)

- Kursas Laiks – Liepāja district newspaper (in Latvian)

- Rožu laukums – Webcam showing "Rose square" in Liepāja

- The murder of the Jews of Liepāja during World War II, at Yad Vashem website

- Liepaja Info – Mobile Application